we continue the master class on anonymous search engines that do not harass the user.

on google everything is clear, on the products of the Russian bottling too, so we are discussing really serious resources

excellent article on the latest data, just copying.

Duckucko go

At one time, DuckDuckGo was presented as an “anti-spyware” alternative to Google, but even a quick analysis with utilities such as lightbeam (an extension for Mozilla Firefox) shows that it does not really respect your personal life. The reason for this was his business model, which mainly relies on commissions from partners. That is, it is not a fact that he manages to earn money without spying on users.

We may refer to this personal information as Non-Public Personal Information. For example, information about where a person works or attends school, as well as which car he or she owns, can be considered personal information in the sense that it is information about an individual as a specific person. For example, seemingly harmless information about individuals based on their activities in the public sphere can be “mined” to create user profiles based on implicit patterns in the data, and these profiles can be used to make important decisions affecting people.

In addition, DuckDuckGo uses Amazon's cloud services as its infrastructure. Although from a technical point of view this decision is justified, it still raises questions given the fact that Amazon is the main provider of cloud services for the CIA and has already obeyed the instructions of the US government (in violation of the first amendment) to remove Wikileaks from the network ... In short, with DuckDuckGo everything is far from as clean as they want to show you.

Zimmer notes that personal information about users is “regularly collected” when they use search engines for their “information operations”. The selected topic, as well as the date and time set by the user for a particular request, are included in the record. Until recently, many people did not know that their searches were recorded and tracked. Other search companies would not say how they reacted; however, many believed that these companies complied with the government agenda.

The information gathered by the user's search queries may seem relatively harmless - after all, who will be interested in learning about what search queries we conduct on the Internet, and who would like to use this information against us? Records of this user's search queries may reveal several searches that are separate about pornographic websites, which, in turn, may suggest that this user is interested in viewing pornography.

Ixquick is an alternative that does not fit into your personal life and offers a DuckDuckGo-like interface. Google served as the inspiration for him, but he is not a search engine in the literal sense of the word, but an aggregator of the results of other search engines. This approach, of course, is interesting, but it can hardly be called a real alternative. He relies on other search engines and makes no contribution to creating a world where you can do without Google.

Search Engines Tor

Thus, individual searches performed by a particular user can theoretically be analyzed in such a way as to create a profile of that user that is inaccurate. And records of search results made by this and other users can subsequently be called to court in court. As already noted, information about user searches is collected by search engine companies, as well as by many different “information traders” in the commercial field.

It is also important to consider whether a significant distinction can be made between monitoring and surveillance in this context. Noting that the two terms are often used interchangeably, Nissenbaum distinguishes them as follows. While supervision is a form of monitoring “from above” by political regimes and authorities, monitoring is used in broader social and “socio-technical” contexts. In Nissenbaum’s scheme, both monitoring and observation are examples of what she calls the “socio-technical context”, but they are usually used for different purposes.

In addition, Qwant, the “made in France” search engine, is one of the systems that do not seek to put your nose into your personal life. Unlike Ixquick, it is a real search engine and uses its own search technology. However, six months ago, he valued his privacy almost more than DuckDuckGo and even used Google Analytics to measure traffic. And this, you see, is a very mixed move if you want to protect the privacy of users.

For example, Nissenbaum points out that monitoring can be carried out by systems “whose clear purpose is to control”. But she also notes that the information itself can be a “way of monitoring." For example, she points out that Clark's concept of “digital surveillance” includes monitoring methods that include both interaction and transactions. However, we can generally consider the practices carried out by information traders in the consumer sphere as examples of monitoring in the sense of Nissenbaum of this term.

But after people drew their attention to this issue (by the way, your humble servant, as well as many hackers, had a hand in this), they nevertheless corrected themselves and installed an alternative to Google Analytics with anonymous proxy servers (they become intermediaries in user interaction with the Internet), which allowed everyone to search the Internet and social networks without transferring any data to Facebook and Twitter.

The Bush administration’s decision to seek information about searches for regular users has been criticized by many privacy advocates. The district court is again reviewed by Congress. He then shows how the reasoning used in the case of libraries can be easily extended to search engines - for example. If the government could see which books someone was taking from the library, why couldn't he also see what searches we did in the search engines?

Medical Information Search

He also fears that such practices may ultimately lead to surveillance and the suppression of political dissent. In this section, we will look at some of the implications that observing user requests from search engines can have for a free and open society. In the early days of the Internet, many people believed that search engine technology favored democracy and democratic ideals.

Like DuckDuckgo, Qwant seeks to establish itself in a growing niche of non-confidential resources and takes the technical side of the matter seriously. To do this, they install proxies (as a result, users can conduct all requests completely anonymously), introduce a standalone and Google-independent traffic estimation system and use logs (the information that remains on the server after the visit) that do not associate your IP with search queries in any way . It turns out that even if the authorities confiscate the equipment, they will not be able to restore your search history by IP address. Some hackers criticized Qwant for not taking an accurate approach to protecting users' personal data, search engine representatives have established contacts with them and are actively developing cooperation to improve their existing technologies. In short, their efforts indicate a serious attitude to the privacy of users. And this is the right approach, because in this area Google will not be able to overshadow Qwant, and DuckDuckGo did not take things seriously and ultimately will pay dearly for it.

Search engines are often described as “cyberspace gatekeepers,” and some critics point out that this has serious implications for democracy. For example, Diaz indicates that. If we believe in the principles of reasonable democracy - and especially if we believe that the Internet is an open "democratic" environment, then we should expect our search engines to spread a wide range of information on any given topic.

Hinman makes a similar point when he notes that "the heyday of deliberative democracy depends on free and undistorted access to information." And since search engines "are increasingly becoming the main gatekeepers of knowledge," Hinman argues that "we are moving in a philosophically dangerous position."

Finally, Google’s alternatives include technology developed by YaCy, a decentralized search engine. It is not for everyone, but in terms of infrastructure we see a truly innovative approach. The flip side of the decentralized system’s coin is that its effectiveness depends on the number of users (such as the speed of downloading files via P2P), in contrast to the centralized systems mentioned above. So far, this technology, of course, is interesting, but it remains the lot of "nerds". Be that as it may, one can imagine the repeated decentralization of the Internet, within the framework of which such a technological approach would have acquired a completely different meaning. In general, this is the only way out of the total control that is forming before our eyes, and therefore YaCy in any case deserves our support.

How to find what Google won’t even search

Morozov also describes some of the problems of democracy in relation to modern search engines, paying attention to the filtering of information that search engines do. And Lessig suggests that any filtering on the Internet be equivalent to censorship, as it blocks some forms of expression.

Morozov is worried about what search companies are now doing with filters and customization schemes, and why this is problematic for democracy, says Parisier, who points out that personalization filters serve as a kind of invisible auto propaganda, inspiring us with our own ideas, reinforcing our desire for familiar things and leaving us without attention to the dangers lurking in the dark territory of the unknown. Parisier notes that while democracy “requires citizens to see things from each other’s point of view,” we instead become increasingly “more withdrawn in our own bubbles.”

Is Google a Hard Drug?

Nevertheless, it will be very difficult for a mere mortal to make such a transition, because everyone has long been irrevocably accustomed to Google. Personally, I try to use another search engine more often in parallel with Google, just like I drag on an electronic cigarette to smoke less than real ones. When I need to find some “sensitive” information that is somehow related to my journalistic investigations, I usually use only Qwant and Ixquick or connect a whole technological arsenal to achieve complete anonymity on the network. But it, as you know, is not available to the average user.

Search engine Ahmia

He further notes that democracy also “requires dependence on general facts,” but instead we present “parallel but separate universes.” He also notes that the search algorithm will generate different results for someone whom he defines as an executor of an oil company versus an environmental activist. Not only do some search engine practices threaten democracy and democratic ideals, others reinforce censorship schemes currently used by non-democratic countries.

Fabrice Epelboin is an entrepreneur and lecturer at the Institute for Political Studies.

Original publication: Les alternatives pour ceux qui veulent se passer de google

Google is the largest and most popular search engine in the world. More than 50 million search queries are logged daily on Google sites, available in approximately 200 languages, and, according to Alexa, Google.com’s main site is the most popular Internet resource. However, despite worldwide recognition and undoubted success, Google is far from being as good as a search engine as it might seem.

For example, it is well known that China has managed to block access to political sites that it considers threatening. He explains that if such a giant search robot could easily be influenced by a government that has relatively low economic consequences for its business as a whole, it could significantly affect the US government, where the political and economic impact will be much greater.

Although many initially believed that the Internet would promote democracy by cutting off totalitarian societies because they were “inefficient and wasteful,” Berners-Lee believes that the Internet, “we have learned,” is now at risk, because both totalitarian and democratic governments “ control people's online habits, jeopardizing important human rights. ” Perhaps Hinman best sums up this concern when he notices.

It's all about universality: it is impossible to search equally well in blogs and in scientific articles, in digital images and recipes. That is why there are many not so well-known specialized search engines that work exclusively with any one category of data, but do it at the highest level.

It would seem that increasing transparency on the part of search engine companies could be an important step in helping to solve some of these problems. We will consider these and related issues in the next section. Let's start with a brief analysis. Elgesem notes that search engines play an important social role as "contributors to the public use of the mind." And we saw that some authors, including Hinman and Diaz, view search engines as the “gatekeepers” of the Web; this factor in itself may entail certain responsibilities for search engines.

Moreover, it’s impossible to find much of what such search engines find using Google and other universal systems: they simply don’t see such information, which, moreover, is often deliberately closed to such “web spiders”.

Let's talk about a few of these "narrow professionals" who are able, perhaps, to open for you that side of the Internet, which you did not even suspect.

Yacy Anonymous Search Engine

Hinman lists four reasons why these companies should have significant social responsibility. Fourth, he points out that the main search engines are owned by private corporations, i.e. “To businesses that are absolutely right in their quest for profit.” Consider some of the ways in which conflicts of this kind have actually arisen in recent years.

Ixquick Anonymous Search Engine

Some critics further believe that conflicts surrounding search engine companies are not limited to prejudices and unfair business practices in the commercial sector, but can also affect the free flow of knowledge in society. We conclude this section by noting that search engine companies still face some critical challenges in fulfilling their role as a “gatekeeper” in a socially responsible way, while protecting both their own algorithms and the interests of their shareholders, to whom they also have legal and moral obligations.

1. Search among deleted from Google and blocked pages

It is no secret that the governments of many countries are trying to influence what kind of network content is available on the territory of their states. This can be explained both by purely political considerations, and by the requirements of the law on countering terrorism and child pornography, and, of course, the influence of lobbyists of large copyright holders. Criteria for prohibitions can be either quite reasonable or completely arbitrary: it all depends on the general state of legal awareness in the country, and on the sanity of law enforcement agencies themselves.

Similarly, search companies believe that if they fulfill official legal requests for “de-indexing” or remove links to sites that willingly and intentionally violate US laws, such as laws that violate copyrights, child pornography, and so on, they should not be legal responsibility for any content that users happen to access through their services. However, many US search engine companies operate internationally, where laws and regulatory schemes differ from laws in the United States.

In most cases, the Google search engine meets the motivated requirements of national governments and removes sites and pages from search results that cannot be accessed through localized versions of the search engine. Meanwhile, removing the address from Google search results and even blocking the URL and IP address at the local provider level does not mean that such a resource has disappeared from the Internet or is no longer available.

Space is our everything

This significant difference in how search engines view the US and Europe has come to the fore in recent debates about whether they should be forgotten. This link concerned an article in a Spanish newspaper on home foreclosure that occurred 16 years ago. Gonzalez, a Spanish citizen, requested the Spanish National Data Protection Agency to remove the link.

For example, they noted that Article 12 of this Directive provides “correction, deletion or blocking of data whose processing does not comply with the provisions of the Directive, since the information is inaccurate”. This special scheme, which can also be considered arbitrary, will continue to be criticized until more systematic guidelines are established for handling user requests.

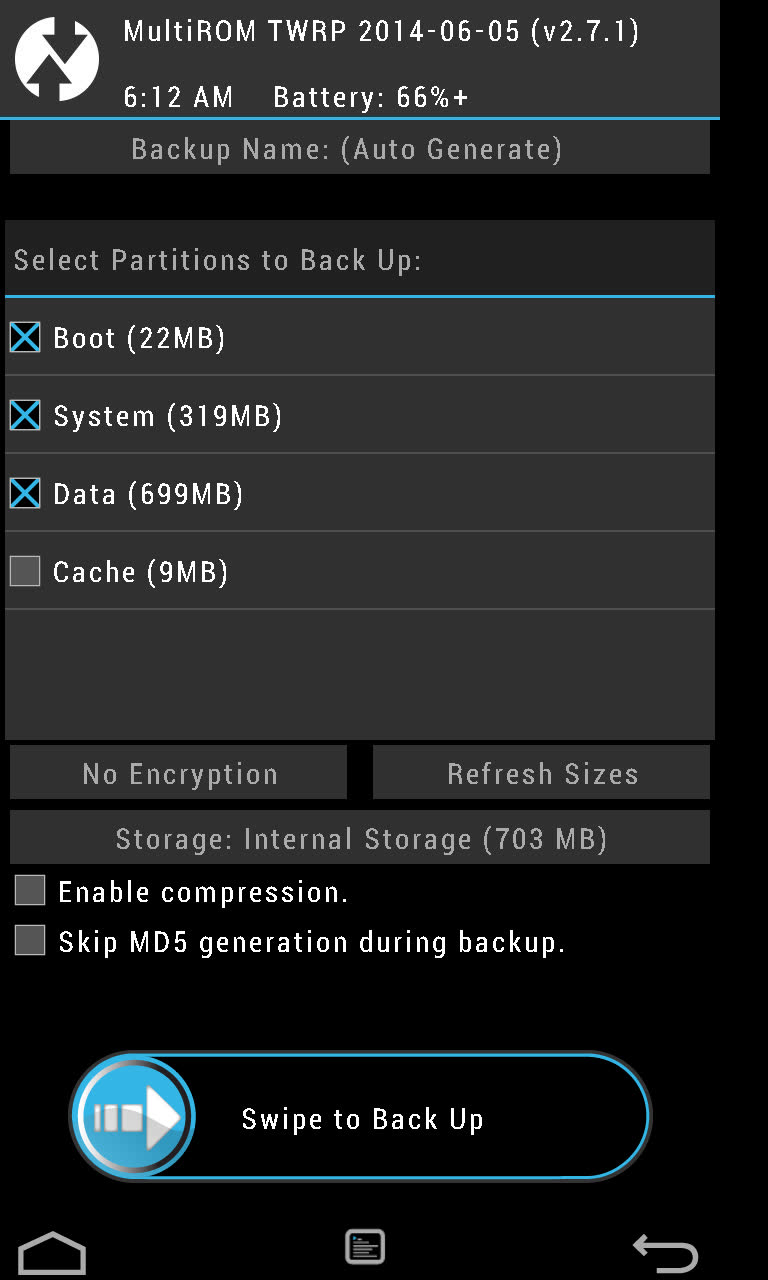

A classic workaround for such restrictions is the Tor browser, which is based on an alternative conventional onion routing system. One of the newest packages, including the Tor client (Vidalia) and the Firefox Portable browser with the foxyproxy extension, bears the quite “talking” name PirateBrowser.

It differs from other similar packages in that it is not intended for completely anonymous surfing: PirateBrowser uses the Tor network exclusively to bypass local blocking of certain pages and sites, substituting arbitrary IP addresses instead of real ones. With it, you can go to a blocked page if you already know its address, or search for it, for example, through the main website Google.com or some other local versions of it.

PirateBrowser already has built-in settings for several countries, including Iran, North Korea, and (surprise!) The UK, the Netherlands, Belgium, Finland, Denmark, Italy and Ireland. Of course, nothing prevents you from adding your own settings to the system. Unfortunately, unlike the full Tor, PirateBrowser is only available in the Windows version.

2. Search among non-existent versions of pages

Many of us used the cache of Google or Yandex to view a recently modified or deleted page in the form in which it was originally published on the Web. Usually, such a cache is available in search results for a rather short time, because the search robot is configured to track and record all changes in order to produce the most current version of the Internet resource.

Therefore, if you want to know what a particular site looked like a month, a year, and even more so a few years ago, you will have to use another tool, namely the Internet Archive web service, which is called Wayback Machine, that is, something something like Time Machine.

Since 1997, the non-profit organization Internet Archive has been collecting copies of web pages, multimedia content, and software posted on the Web, and makes these copies available for free to everyone. With the help of Wayback Machine you can find not only a version of a site you know many years ago, but even those pages that have not existed for a long time and which are simply removed from the "normal" Internet.

Today, the archive contains about 366 billion pages, and it is very likely that among them will be what you need.

3. Image Search

The most common way to find a picture is, of course, use Google Images. But what if you still could not find a suitable image with the usual means? You can, for example, try the specialized service Picsearch, in which, according to its creators, more than three billion digital images are indexed.

Picsearch has not only a multilingual user interface, but also a full multilingual search, as well as several useful filters, including searching only black and white or color images, images with a predominance of a particular color, searching for “wallpapers” for the desktop, as well as faces or animated images.

The Everystockphoto search engine boasts a much smaller declared index base: it contains more than 20 million images stored on online photosites, including Flickr, Fotolia and Wikimedia Commons. Nevertheless, the results of her work are very impressive. Most of the images found can be used free of charge, but subject to the name of the photographer or copyright holder.

4. Computer search engine

As you know, the Google search system can perform simple calculations, convert from one unit to another and do some other useful things that are not directly related to the search. However, if you need answers to really complex questions in the field of mathematics, physics, medicine, statistics, history, linguistics and other areas of science, then you can not do without the "computer-search system" WolframAlpha, able to offer the user almost encyclopedic answers to the most unusual questions.

In fact, this is not even quite a search engine, but a huge database, part of which is converted into computational algorithms, which allows you to get ready-made information about how many grams of protein are contained in a dozen M & M's sweets, what is the expected average life expectancy in the USA, Sweden and Japan in current year or how the algebraic equation is solved.

Instead of describing the functionality of WolframAlpha for a long time, we suggest that you go to the examples page, which contains samples sorted by area of \u200b\u200bknowledge of what kind of questions this system can answer and what the results will look like.

Unfortunately, WolframAlpha only works with English, and to use it you will need a fairly confident knowledge of it. In addition, you should not blindly trust the results that the system calculates according to your requests, since the slightest error in the database leads to complete inaccuracy of the issue, and this happens periodically (just search on the Web).

5. Search for people

It would seem that finding a person on the Internet, knowing his name and surname, is simple. Yes, if it's some kind of celebrity, movie star, athlete or regular user of social networks. Then the very first page of Google search results will give you almost comprehensive information about who he is and what he has been doing lately. If the person you are looking for does not crave wide popularity and is not interested in network exhibitionism, finding information about him on the Internet will not be so simple.

In this case, you can try the Pipl search engine, which searches for people in a number of public registries, online databases, services, and yet in social networks, including professional ones. Unlike most of these services, Pipl also works with the Cyrillic alphabet, so it is quite functional with Russian-speaking surnames.

The Russian service SpravkaRU.NET will help you find the address and home phone number of a resident of Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Latvia and Moldova. This site is an electronic telephone directory of some major cities of these countries, but, alas, far from complete. More likely to find residents of Moscow or St. Petersburg, and only those who have a home number.

Unlike alternative services, SpravkaRU.NET contains quite up-to-date databases, and if you have at least some information about relatives or the approximate place of residence of the wanted person, then he can help you establish his phone number and address.

6. Search for scientific information

If you are engaged in science and want to find the latest scientific publications on your topic on Google, then you urgently need to forget about discoveries and do something less intellectual. In Google, you can only find links to individual works published on some public sites like Wikipedia. In fact, almost all scientific articles are stored on web servers belonging to the category of the so-called deep web, which for various reasons is not available for universal search engines.

The whole point is the compulsory ban on indexing any data that, although not classified as secret, constitutes some kind of official information or is not of interest to the general public. These are library catalogs, medical or transport databases, and catalogs of various industrial products. Spiders cannot get around the system of compulsory registration or restriction of access, so you rarely see scientific materials in Google’s results that are simply incomprehensible to people who don’t do similar research.

The specialized Search Engine CompletePlanet, with access to more than 70,000 scientific databases and narrowly targeted search engines, can open the door to the scientific “deep web”.

Another excellent scientific search engine Scirus, unfortunately, is living out its last weeks: at the beginning of 2014 it will cease to exist, and regular users are invited to find an alternative (which, alas, is not clear) in the remaining time. In the meantime, Scirus has access to many archives of scientific articles and allows you to search for information on 575 million problems, including publications in highly specialized and popular science journals, patent texts, and information from digital archives.

The existence of specialized search engines does not at all negate the merits of universal search engines: we can’t do without them anyway. But a true professional does not use a hammer where a screwdriver is needed, or a knife where a scalpel is appropriate. Special systems allow for a finer search and therefore are able to give more accurate and reliable answers.